London Poems is a slim volume written by a middle-aged English fat bloke. The poems were composed in London, about places in London and in reference to feelings that emerged as the writer found himself processing random thoughts in or near London.

The subjects of the poems are those, pretty much, that have preoccupied practitioners since the year dot. They are about love, loss,self-examination, and the woes of the world. A few more uplifting verses are chucked in to deflect accusations of rank melancholy.

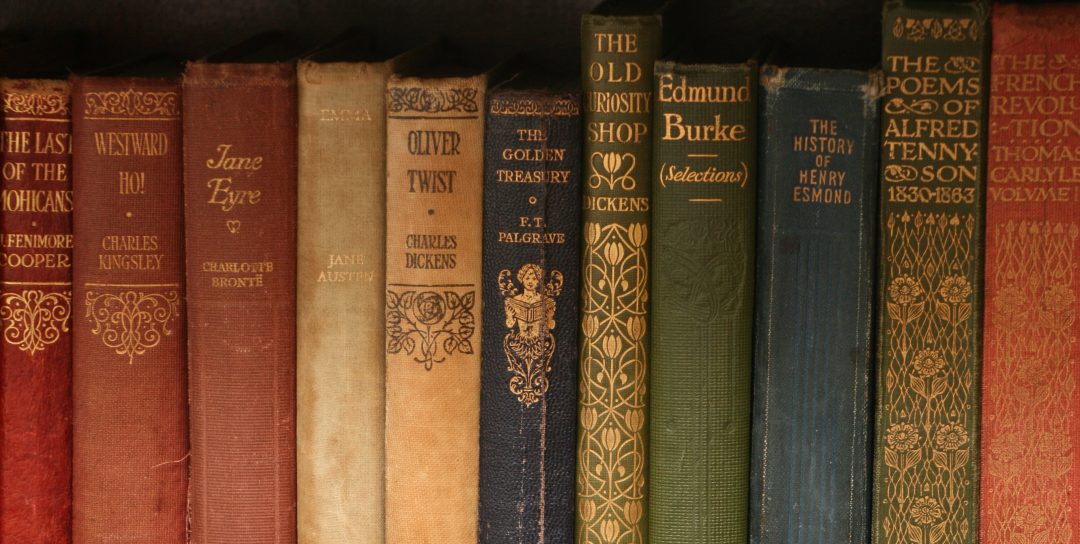

Readers may spot the poets of the great tradition to whom debts are owed. One of the writer’s methods is to match the occasional overflow of powerful feelings to a poem from the canon. It doesn’t matter whether readers’get’these references. It is appropriate, however, to give credit where it is due.

Robert is especially indebted to Elizabeth Browning, William Blake, Gaius Valerius Catullus, John Cooper Clarke, Wendy Cope, Emily Dickinson, TS Eliot, UA Fanthorpe, Stephen Fry, Thomas Gray, Thomas Hardy,Tony Harrison, AE Housman, Patrick Kavanagh, Clive James, John Keats, Philip Larkin, John Milton, Adrian Mitchell, Ruth Pitter, Dylan Thomas, Wilfred Owen, Brian Patten, Christina Rossetti, VikramSeth, William Shakespeare, Oscar Wilde, WB Yeats, and Benjamin Zephaniah.

Recent Comments